The expanding conflict in Ethiopia has resulted in damage to schools and educational institutions, with the country’s education ministry stating that 1.42 million students have been unable to attend classes in the Tigray region. But the deteriorating situation has also impacted an unlikely group of people—the hundreds of Indian professors who teach in institutions of higher learning across the country.

When the conflict broke out last November, Professor Sandeep Mishra was teaching at Adigrat University in Tigray. The rapidly deteriorating situation in the region resulted in closures of public spaces and institutions that had already been facing difficulties brought on due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

“For close to two years, classes haven’t been held. First they closed due to Covid-19, and then elections started, which were followed by the conflict in November. Classes were held for only two to three months and we somehow managed to grade student papers,” said Mishra.

The suspension of classes and the escalating conflict in Ethiopia compelled many Indian educators, most of whom teach in colleges and universities, to return to India. While exact figures were not immediately available, Mishra estimates that some 2,000 Indians presently work as professors in the country, of which approximately 120 work across Tigray’s four major universities. After the start of the conflict, universities and colleges in Tigray shut down, forcing Indians in the region to return home.

Indian professor Dr. Vivek Biswas with his students during a class at the Ethiopian Civil Service University in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 2017. Photo credit: Dr. Vivek Biswas/Facebook

Indian professor Dr. Vivek Biswas with his students during a class at the Ethiopian Civil Service University in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 2017. Photo credit: Dr. Vivek Biswas/Facebook

But even before the conflict erupted, a combination of economic factors in the country had been making it difficult for Indian educators to continue working there. “The inflation and political and economic instability has resulted in changes in the salary,” Mishra said. In 2018, without prior notice, foreign academics learned that they were going to see a reduction in their pay, where a salary cut of 35 percent would be imposed on their annual income, a decision that local news reports had said was driven by foreign currency shortages in the country.

At that time, Ethiopian government figures had estimated that some 2,000 Indian nationals were teaching in institutions across the country, the largest group of foreign academics by country. “So if we got USD 2,500 as salary, that entire amount would be handed to us. Converted to Indian rupees, it was a lot of money,” said Mishra. The domestic developments in Ethiopia have driven up everyday costs, leaving Indian educators little money to send back home. “What is left in our hands is sometimes less than the salary some teachers make in India.”

Despite those difficulties, several academics interviewed by The Indian Express for this report said that they genuinely enjoyed their work in Ethiopia. “It was a difficult decision to come back to India. Not just for me, but also for other Indians who worked there,” said Dr. Zubeirul Islam, who teaches geography at Adigrat University.

Favourable work conditions, the climate, and the respect given especially to Indian teachers are some reasons why they prefer to work in Ethiopia, academics told The Indian Express. “They make us feel like we are a part of their community and that is why we like it there. We get so much affection there. That is lacking in India. This is why we are even able to stay in the country,” said Islam.

Indian educators have historically played an important role in Ethiopia, Robert Shetkintong, India’s Ambassador in Addis Ababa, told The Indian Express. “The first batch of Indian teachers went to Ethiopia from Kerala in the 1950s,” said Muralidharan Nair, who spent nearly three decades as a teacher and principal at various institutions in the country, before returning to India in 2011. The recruitment was a part of Emperor Haile Selassie’s policy of westernisation that focused on ensuring fluency in English in Ethiopia and sought language trainers from the West.

In this photograph, Muralidharan Nair stands with a colleague in front of a banner of the Indian Community School in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Photo credit: Murlidharan Nair

In this photograph, Muralidharan Nair stands with a colleague in front of a banner of the Indian Community School in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Photo credit: Murlidharan Nair

There were several stumbling blocks in the implementation of those plans. Educators from the West demanded high salaries that Ethiopia could not afford at that time, compelling Haile Selassie to turn to India, Nair said. A legacy of British colonialism, English was the medium of instruction in several public and private schools in India, particularly in urban centres. Hence, in India, Ethiopia found teachers who would be able to impart education in English across age groups at lower salaries than their western counterparts.

The first wave of recruitment of Indian teachers was handed over to the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, which had strong connections with the Indian Orthodox churches, predominantly in Kerala, said Nair. As word spread of opportunity in these distant lands, teachers across India began responding to recruitment advertisements for employment in primary schools, conducted directly under the supervision of the Ethiopian embassy in New Delhi.

The exterior of the building that housed the Indian Community School between 1976 to 1997 in Ethiopia. Photo credit: Meaza Mesfin

The exterior of the building that housed the Indian Community School between 1976 to 1997 in Ethiopia. Photo credit: Meaza Mesfin

By the time Nair arrived in Ethiopia in 1980, Soviet-backed Mengitsu Haile Mariam and his supporters had deposed Emperor Haile Selassie and had established a socialist regime six years prior. “That was really the peak, with the maximum number of Indian teachers working in Ethiopia. The socialist government was recruiting for teaching secondary and senior secondary students (classes 9 to 12),” Nair recalled.

Indians were posted not just in the capital Addis Ababa, but they were also recruited for teaching positions in schools in smaller towns and remote villages, a trend that lasted for more than five decades. At that time, Indians began travelling to Ethiopia in such large numbers, many with their families, that the Indian community established two schools, the Indian National School in 1946, and the Indian Community School in 1976, in Addis Ababa, that operated under the supervision of the Indian embassy with the CBSE curriculum, for the community’s children.

An undated photo of an early batch of students at the Indian National School, Ethiopia. In the last row, at least one Indian teacher is clearly visible. Photo credit: Anteneh Genene

An undated photo of an early batch of students at the Indian National School, Ethiopia. In the last row, at least one Indian teacher is clearly visible. Photo credit: Anteneh Genene

As word spread of the quality of education and fees that were comparatively more affordable than the American and British schools, demand from Ethiopians led to the government allowing the Indian schools to admit Ethiopian students. In 2002 however, domestic complications and controversy resulted in the Indian Community School getting shut down. Some 15 years later, the Indian National School that had been established before India’s Independence also closed down in 2017, Nair said, declining to give details.

“Perhaps, there was not a single person in Ethiopia of that generation who had not been taught by an Indian teacher,” said Shetkintong. Post the 1990s, Ethiopian teachers began replacing them in schools, with Indians getting hired mostly for teaching positions in colleges and universities.

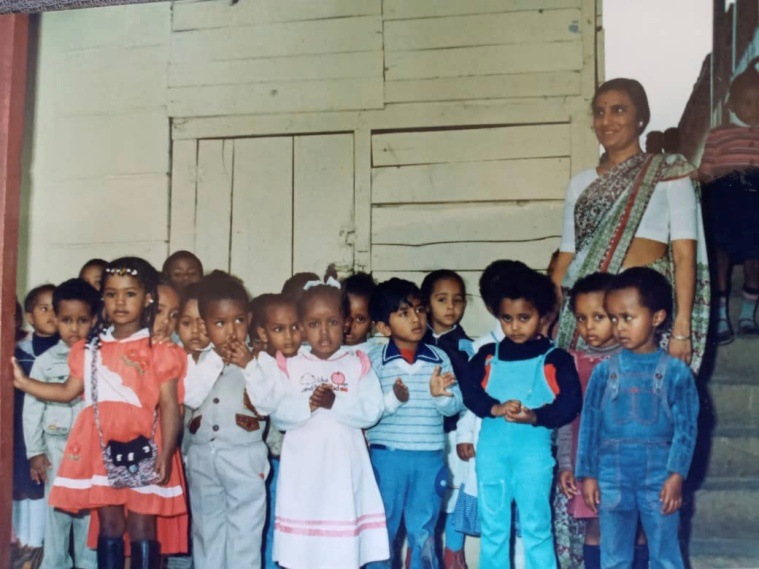

Mezgebwa Tedessa (orange dress) stands with the classmates and her Indian teacher during a class photo in 1983 at the Indian National School in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Photo credit: Mezgebwa Tedessa

Mezgebwa Tedessa (orange dress) stands with the classmates and her Indian teacher during a class photo in 1983 at the Indian National School in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Photo credit: Mezgebwa Tedessa

“By the time people of our generation got to schools, there were quite a few Indians teaching, and not just in primary schools and high schools, but also universities,” said 40-year-old Mezgebwa Tedessa, speaking from her Addis Ababa home. “My father would have been in his 80s now had he not passed away, and he had Indian teachers in primary school in Agaro, which is 700 kms from Addis. That would have been in the 1940s.”

Now in her 70s, Tirufat Gebereyes Kurfa does not fully remember the names of all her Indian teachers, but some memories are vivid in her mind. “The first time I met Indian teachers was when I started 7th grade in 1964 at Empress Menen High School. The head director was a woman named Lielt Hirut Desta, the direct granddaughter of Emperor Haile Selassie, but the second director was an Indian lady whom I only knew as Mrs. Vergis,” Kurfa recalled. “From what I remember, my biology and physics teachers were also Indian women.”

Like other members of her family, Tedessa’s husband studied in three different towns across Ethiopia, some nearly 500 km away from the capital, where he was taught by Indian educators wherever he went. “So Indian teachers were present everywhere,” she said.

Indian educators were held in high regard in the country, people interviewed for this report told The Indian Express. That has not changed, they said, in part because of respect and acknowledgement of the teachers’ contributions to Ethiopia’s education system over the decades. “If an Ethiopian saw an Indian they would immediately say ‘Hind Astamari’. ‘Astamari’ means teacher in Amharic and all Indians are called ‘Hind’. The synonym for the word ‘Indian’ was ‘teacher’,” said Nair.

“If you go to any office, there will be at least one person who has been taught by Indians. Many government officials and diplomats were taught by Indians. My student is the current foreign minister. Indian teachers were respected there, more than the respect we get here,” he said.

Despite the challenges that Indian academics have faced over the past few years, compelling some to seek opportunities elsewhere, for others, it is the personal relationships that they have developed with the people of Ethiopia and the goodwill that the educators have earned that keeps drawing them back to the country. At the same time, the uncertainty of what the future holds due to the conflict worries them.

This past year, when the fighting escalated, like many of his colleagues, Mishra found himself hurriedly leaving for India. “I have come back to India with unpaid bills pending with vendors. Despite the domestic situation, the people really cooperated with us because they knew we couldn’t access bank accounts,” Mishra said. “I found good human beings across Ethiopia.”

Such is the draw that there are many Indians anxiously waiting to go back to their jobs. Those working in other Ethiopian states who had left when the conflict escalated, have been booking flights to return to work where universities are open. “Everyone was disappointed when we had to come back. Academics in Tigray had to leave, but some teaching in other states stayed back. We don’t know when we can return,” said Islam.

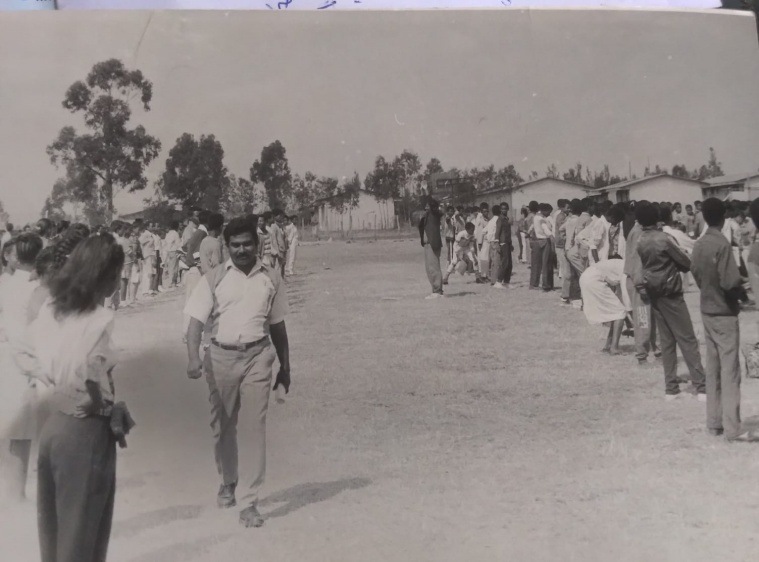

Murlidharan Nair on the grounds of a senior secondary government school in Bole, Ethiopia where he was teaching in 1984. Photo credit: Murlidharan Nair

Murlidharan Nair on the grounds of a senior secondary government school in Bole, Ethiopia where he was teaching in 1984. Photo credit: Murlidharan Nair

Mishra recalled a colleague recently asking him for advice regarding a job opportunity that had opened up at an Ethiopian university. “The (job) situation is so terrible in India that going to work in Ethiopia is much better. People prefer to go there despite the tax challenges and the conflict. The weather is good. There is a lot of respect given to professors there. Before the conflict erupted, it was relatively peaceful,” explained Mishra.

A photograph of the 1983 batch of Indian and Ethiopian students in Grade 1, with their Indian teachers at the Indian National School in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Photo credit: Daniel Teklemariam

A photograph of the 1983 batch of Indian and Ethiopian students in Grade 1, with their Indian teachers at the Indian National School in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Photo credit: Daniel Teklemariam

Having been educated by Indian teachers most of her life, Tedessa believes that she may just be biased towards them and the role they have played in the country. “I feel they bring something different—different experiences, something extra that is not available in Ethiopia, on top of the education that they bring. I want to say that their absence will impact the education system. I believe there are enough teachers that can fill that void, but I don’t know if they would be of the same calibre,” she said.