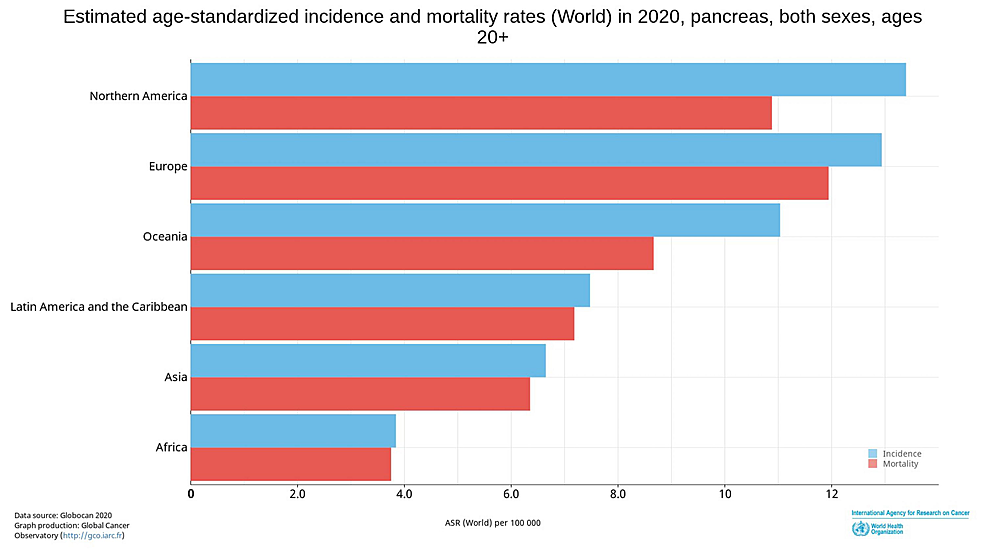

Pancreatic cancer comprises 3.2% of all new cancer cases in North America and 3% of cases worldwide. Mortality is approximately 8% of all cancer deaths in North America and 5% worldwide, making it the third most common cause of cancer death in the United States and seventh worldwide [1]. Estimated age-standardized incidence and mortality are higher among North American and European populations in comparison to the rest of the world (Figure 1) [1]. Overall, 82% of patients are diagnosed with an advanced-stage disease on presentation, with abysmal five-year overall survival of approximately 9% [2]. Traditional chemotherapy has been the mainstay treatment with limited improvement in survival, necessitating the need to identify targetable agents to significantly impact survival. Relatively successful strategies with agents targeting the DNA damage repair (DDR) mechanism, especially among patients with breast cancer-associated (BRCA) mutations, are being examined in the setting of pancreatic cancer.

Incidence of DNA damage repair genes

Pancreatic cancer is largely sporadic, with 5-20% of patients having a germline predisposition [3-7]. Genetic mutations of damaged DNA repair genes such as BRCA1/2, partner and localizer of BRCA2 (PALB2), and the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) gene along with the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) gene (familial atypical multiple mole and melanoma syndrome) and mismatch repair genes (Lynch syndrome) are associated with significantly increased risk of pancreatic cancer. BRCA1 is seen in up to 2.4% of pancreatic cancer patients, with up to a three-fold higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer [3,8]. BRCA2 mutations are seen in about 6% in sporadic and up to 17% in familial pancreatic cancer, with an even higher incidence in the Ashkenazi Jewish population [3,7-10]. BRCA2-mutated patients have a 3.5-6-fold higher risk for developing pancreatic cancer [11,12]. PALB2 is reported to occur in 2-4.9% of familial pancreatic cancer patients and 0.5% sporadically [9,13-15]. ATM mutations have been reported to occur in 2.4% of familial pancreatic cancer patients [16] and 3-4% in a study with a population unselected for family history of cancer [9,17]. Checkpoint kinase 2 (CHEK2) has been observed in up to 4% of patients and CDKN2A in 1.7% of patients [4,9,18-20]. A summary of the above mutations has been presented in Table 1.

Synthetic lethality and DNA damage repair

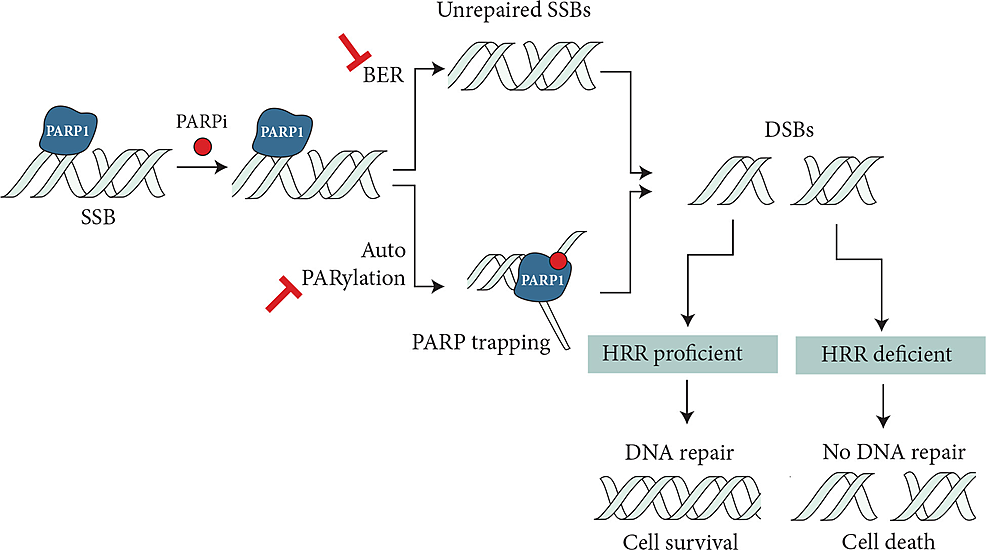

The synthetic lethality concept was first introduced by Bryant et al. [21] and Farmer et al. in 2005 [22], which explains synergistic genetic mutations in two or more genes leading to cellular death. There are many DNA repair mechanisms that help restore genetic integrity in cells as well as common repair pathways that sense single-stranded DNA breaks are base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, and mismatch repair. If the single-stranded break repair is not effective, it leads to the formation of double-stranded DNA breaks. Double-stranded DNA breaks are repaired through homologous recombination (HR) during the last phase of the S and G2 phases of cell cycles and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) during the G1 phase [23]. Based on this concept, several targeted therapies against tumor-specific gene defects have been used to kill cancer cells. Poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors use the concept of synthetic lethality to target BRCA mutations.

PARP1 senses DNA damage and binds to the region of DNA breaks, inducing signal transduction by producing PAR chains (autoPARylation) on target proteins. PAR chains attract DNA repair effectors, thereby competing for DNA repair [24]. PARP inhibitors trap PARP1 through inhibition of autoPARylation with or without PARP release, which in the presence of HR deficiency leads to the accumulation of double-stranded DNA breaks and ultimately to cell death (Figure 2). Cells lacking BRCA1/2 and PALB2 are predominantly affected by PARP inhibition. Platinum agents create DNA cross-links, disrupting DNA functions, which is further potentiated by the lack of a DNA repair mechanism. Platinum agents are preferred in BRCA-mutated patients as they have been shown to significantly improve overall survival in the advanced or metastatic disease setting [25]. Single-strand breaks, which are repaired through the base excision pathway, are also inhibited by PARP inhibitors, resulting in cell death in HR-deficient cells. Multiple PARP inhibitors are currently available with different PARP trapping potencies.

PARP inhibitors

Following the detailed introduction, PARP inhibitors sensitize cancer cells to DNA damaging therapies and inhibit DNA repair mechanisms leading to synthetic lethality. Several clinical trials such as the OlampiAD study for breast cancer [26], SOLO study for ovarian cancer [27], and TOPARP-B study for prostate cancers [28] with underlying germline BRCA1/2 mutations have shown promising results with an increase in response rate and progression-free survival (PFS). According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) practice guidelines, germline testing is recommended for all patients with confirmed pancreatic cancer [29]. The effectiveness of PARP inhibitors can be examined in cancers that possess BRCAness gene defects. BRCAness can be described as tumors that do not have germline line BRCA mutation but have gene defects that share phenotypic similarities with BRCA mutations and have defective HRR. This review focuses mainly on the clinical trials of several PARP inhibitors to date and those currently underway to assess the efficacy of PARP inhibitors in the treatment of pancreatic cancer (Table 2) [30-32].

Olaparib

Olaparib is currently the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved PARP inhibitor for use in pancreatic cancer. Multiple clinical trials are underway evaluating olaparib use for pancreatic cancer both as a monotherapy and combination therapy (Tables 3, 4). FDA approval was based on the POLO trial, a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study that evaluated the efficacy of olaparib as maintenance therapy [33]. In this study, a total of 154 patients had germline BRCA1 or BRCA2-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer without disease progression during at least 16 weeks of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. In the study, 92 patients received olaparib and had significantly improved median PFS of 7.4 months versus 3.8 months in the placebo group (p = 0.004). At two years, 22.1% in the olaparib group had no disease progression in comparison to 9.6% of patients in the placebo group. However, planned interim analysis at 46% data maturation showed no difference in OS between the groups. There were certain limitations to the study. Included trial patients had a good response to the platinum agents prior to maintenance PARP treatment and non-responders were not included. Maintenance chemotherapy after six months of intense triple chemotherapy in responders is a common strategy employed with single-agent 5-fluorouracil or capecitabine versus combination with irinotecan or platinum agents, unlike placebo in the control arm. Overall, this study paved the way for multiple therapeutic and maintenance strategies in pancreatic cancer patients.

Olaparib as monotherapy: Two ongoing parallel phase 2 trials [34] in the United States (NCT02677038) and Israel (NCT02511223) are evaluating the efficacy of olaparib in advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with BRCAness (excluding germline BRCA1/2 mutations) after at least one prior systemic therapy regimen. Of the 11 U.S. patients, two achieved partial response (PR), six reported stable disease (SD), and three have experienced progressive disease (PD), with a median PFS up to 24.7 weeks. Of the 21 Israeli patients, five are with SD, and 12 are with PD, with a median PFS of 14 weeks. Another phase 2, open-label study assessed the efficacy and safety of olaparib in 23 advanced pancreatic cancer patients with confirmed genetic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (NCT01078662) [35]. Over 74% of patients with BRCA2 mutations with a mean of two prior therapies with 65% receiving prior platinum. Overall, 22% of patients had a complete response (CR) or PR, and 35% had SD at eight weeks. The response was independent of BRCA1/2 status as well as response to prior platinum treatment. Median PFS was 4.5 months with a median OS of 9.8 months at the end of the study. OS rate at 12 months was 41%.

Olaparib with chemotherapy, other targeted therapies: NCT00515866 is a phase I study of olaparib with gemcitabine in patients with advanced solid tumors to evaluate the safety and maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of the combination for pancreatic cancer treatment [36]. A total of 68 patients were included in the dose-escalation and expansion phase, with more than 81% of patients with combination treatment experiencing grade ≥3 adverse events, predominantly cytopenias (55%). Based on this study, the ideal combination was olaparib 100 mg twice daily (intermittent dosing) with gemcitabine 600 mg/m2 with manageable toxicities. NCT01296763 [37] is another phase 1 dose-escalation trial evaluating olaparib in combination with irinotecan, cisplatin, and mitomycin C in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Unfortunately, patients in this trial developed significant toxicity with this combination therapy, predominantly cytopenias, resulting in early study closure.

NCT03682289 [38] is a non-randomized phase II trial studying the efficacy of ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) kinase inhibitor AZD6738 alone or in combination with olaparib in patients with advanced renal cell, urothelial, and pancreatic cancers. Patients tested for BAF250a positive expression on immunohistochemistry received AZD6738 in combination with olaparib. BAF250a-negative or ATM-mutant patients received AZD6738 only. NCT02498613 [39] is an open-label phase II trial studying cediranib maleate (vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)) combined with olaparib in advanced breast, non-small-cell and small-cell lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer patients. Apart from the primary objective to assess the response to the treatment, other exploratory objectives include the correlation of response to DNA repair gene mutations, estimating levels of angiogenesis markers such as VEGF at baseline and after treatment, evaluating tumor hypoxia in lung cancer patients, and circulation tumor DNA measures through treatment course. This study unfortunately did not show any meaningful activity.

Other ongoing trials are NCT03205176 [40], a phase I, multicenter, dose-escalation study evaluating AZD5153 (bivalent BRD4/BET bromodomain inhibitor) pharmacokinetics, anti-tumor activity with tolerability both as a monotherapy and in combination with olaparib in patients with relapsed/refractory malignant solid tumors and lymphomas. NCT04005690 [41] is a phase II trial evaluating how cobimetinib or olaparib works in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer by comparing pretreatment biopsy samples with posttreatment resection specimens. The primary goal is to use the results in designing future biomarker-driven trials.

Olaparib with immunotherapy: NCT03851614 [42] (DAPPER) is a phase II basket study in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, mismatch repair colorectal cancer, and leiomyosarcoma to evaluate changes in genomic and immune biomarkers in the tumor, peripheral blood, and stool samples. The study involves a combination of durvalumab (programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)) with olaparib or cediranib (AZD2171, a small-molecule VEGF-TKI). This study is still ongoing, and results have not been published yet.

Veliparib

Veliparib as monotherapy: There are nine clinical studies involving veliparib (Tables 5, 6). Monotherapy was evaluated as a phase 1 study (NCT00892736) in patients with refractory BRCA1/2-mutated solid cancer; platinum-refractory ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer; or basal-like breast cancer. At the MTD, BRCA-positive patients had a response rate of 58%. This study had a limited number of pancreatic cancer patients, and specific data regarding pancreatic cancer outcomes were not available [43].

Veliparib with chemotherapy: NCT01908478 is a phase I study evaluating veliparib (ABT-888) in combination with gemcitabine and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in patients with locally advanced and unresectable pancreatic cancer. This study among 30 patients showed a median OS of 15 months. There were no BRCA patients in the trial. Interestingly, median OS for DDR pathway gene-altered was 19 months and 14 months among DDR-intact patients. Increased expression of the DDR proteins PARP3 showed significantly improved OS; however, DDR pathway mutations did not correlate with OS [44]. The majority of patients had SD (93%), with PR in one patient.

NCT01489865 is a phase I/II study of veliparib in combination with 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. According to the final study results, of the 64 patients, 78% were platinum-naïve, 69% had a family history, and 27% had DDR mutations. Among the total 57 evaluable patients, the objective response rate (ORR) was 26% with median PFS of 3.7 months and median OS of 8.7 months. However, in patients with DDR mutations, ORR (58%) and m PFS (7.2 months) doubled with improvement in OS (11.1 months). The responses further improved in patients with family history and platinum-naïve disease along with DDR deficiency, which appears to be a promising combination with respect to the safety and response in metastatic PDAC [45]. An earlier report from the trial mentioned, two BRCA2 patients were included in the study, one had a PR at 17 months, and the other had CR with normalization of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 at 10 months.

NCT01585805 is a randomized, phase II study of gemcitabine, cisplatin without (Arm A) or with (Arm B) veliparib, and a phase II single-arm study of single-agent veliparib in patients with BRCA– or PALB2-mutated pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Among the enrolled 55 patients, median PFS (~10 months) and median OS (~16 months) were not significantly improved with the addition of veliparib [46].

NCT02890355 is a randomized, phase II study evaluating second-line modified FOLFIRI with veliparib versus FOLFIRI. Out of 143 patients included in the analysis, 30% had DNA repair gene abnormalities and 9% has HR deficiency. Interim futility analysis at 35% of expected PFS events showed that the veliparib arm was unlikely to be superior to control in the biomarker unselected population. Median PFS was approximately two to three and median OS was five to six months. Biomarker-driven efficacy is yet to be published [47]. NCT01233505 is a phase I study evaluating veliparib in combination with oxaliplatin and capecitabine in advanced solid tumors. The trial included one patient with pancreatic cancer who had SD with this combination [48].

NCT00576654 is a phase I study designed to evaluate the safety and preliminary efficacy of veliparib (ABT-888) in combination with Irinotecan among advanced solid tumors. Safety of combination was established, and PR is observed in approximately 19% of patients. However, no pancreatic cancer patients were reported in the study [49].

Rucaparib

According to the literature, four clinical trials have been reported, two as monotherapy, and two as combination therapy. NCT03140670 is a phase II trial of rucaparib evaluating patients with advanced pancreatic cancer with known germline or somatic BRCA or PALB2 mutations who had not progressed on at least 16 weeks of platinum treatment. Out of 24 patients enrolled, 13 had germline BRCA2, three had germline BRCA1, two had germline PALB2, and one had somatic BRCA2 mutation. Median PFS was 9.1 months from starting rucaparib therapy, with an ORR of 36.8% and disease control rate (CR + PR + SD) of 89.5% for at least eight weeks [50]. Overall, the study showed encouraging results that maintenance strategy not only for germline BRCA, as in POLO trial, but in other germline and somatic mutations might be an effective strategy.

NCT02042378 (RUCAPANC) evaluated the efficacy of rucaparib monotherapy in patients with pancreatic cancer with deleterious BRCA mutations. Sixteen of nineteen BRCA1/2 mutations were germline, and three were somatic BRCA2. There were two PR, one CR, with an ORR of 15.8%, and further enrollment was halted in view of the poor response rate [51].

Rucaparib with chemotherapy: NCT03337087 [52] is a phase Ib/II trial evaluating safety along with the efficacy of liposomal irinotecan and fluorouracil with rucaparib in patients with advanced pancreatic, colorectal, biliary, and gastroesophageal cancers. Patients with pancreatic cancer could have received up to two lines of prior therapy. This is planned to evaluate responses based on the HRD mutation status. NCT04171700 [53] is a phase II study of rucaparib as a treatment for solid tumors with deleterious HRD mutations including pancreatic cancer patients. Currently, no published data are available for both studies.

Rucaparib with other targeted therapies: NCT02711137 [54] is an open-label phase I/II dose-escalation/expansion along with safety and tolerability study of INCB057643 bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) inhibitor as a single agent and in combination with multiple interventions, including rucaparib in patients with advanced malignancies. The study is currently terminated in view of safety issues. Table 7 lists the trials involving rucaparib as maintenance therapy, monotherapy, and combination therapy.

Talazoparib

Talazoparib is a selective oral PARPi that is more potent than earlier PARP inhibitors (Table 8). NCT01286987 is a phase I, first-in-human study of talazoparib in patients with advanced or recurrent solid tumors to evaluate antitumor activity and MTD of talazoparib. The study included 13 patients with pancreatic cancer; four out of 13 patients have shown clinical benefit (CR + PR + SD = 31% ≥16 weeks), with 20% (two patients) having PR. Among patients with PR, one had BRCA2 and another had PALB2 mutations. The maximum tolerated dose was found to be 1 mg/day [55]. NCT03637491 [56] is an ongoing phase 1b/II study evaluating the safety and efficacy of avelumab, binimetinib, and talazoparib combination in patients with locally advanced or metastatic Ras-mutant solid tumors including pancreatic cancer patients. DDR mutations will be assessed at baseline. Objective response and dose-limiting toxicities are considered as primary outcomes. Unfortunately, the study was terminated as there was limited antitumor activity, and reaching target study drug dose levels was not feasible.

Niraparib

There are three ongoing trials of niraparib (two monotherapy and one combination therapy trial). NCT03601923 [57] is a phase 2, proof-of-concept trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of niraparib in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer with germline and somatic HRD mutations. Included patients received at least one line of treatment for their cancer and did not have cancer progression on an oxaliplatin regimen (similar to FOLFIRINOX or FOLFOX). Palliative radiation will be started at least a week before the initiation of niraparib. PFS is the primary outcome of the study, and overall response and survival rate are the secondary outcomes. NIRA-PANC (NCT03553004) [58] is a phase II trial evaluating the efficacy of niraparib in metastatic pancreatic cancer patients with germline or somatic HRD mutations who received at least one prior line of therapy. Currently, patients are actively being enrolled. ORR (overall response to therapy at eight weeks) is the primary outcome, and PFS and OS are the secondary outcomes. Currently, no published data are available for these studies.

Niraparib as combination therapy (with immunotherapy): Parpvax (NCT03404960) is a phase Ib/II study of niraparib plus ipilimumab (phase 2), niraparib plus nivolumab (phase 1) evaluating the safety, effectiveness, and antitumor activity (preventing tumor growth) in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer whose disease has not progressed on platinum-based therapy for at least 16 weeks [59]. PFS is the primary outcome of this trial. This study is actively recruiting patients (Table 9).

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer continues to be one of the most difficult cancer to treat with chemotherapy as the predominant first-line treatment. Immunotherapy was granted accelerated FDA approval in 2017 for MSI-high/MMR-deficient advanced solid tumor patients, and larotrectinib/entrectinib is currently approved for neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase gene fusion-positive patients. These therapies are currently recommended by the NCCN guidelines in patients with poor performance as firstline [29]. Targeting the DNA repair mechanism is one of the novel approaches in the treatment of pancreatic cancer, and PARP inhibitors are at the forefront of that approach. Apart from germline BRCA1/2 patients, multiple genetic defects affecting the DNR repair mechanism mentioned as BRCAness are currently under investigation in several cancers with PARP inhibitor therapy.

The most significant success, along with the first FDA approval, was through olaparib (POLO trial) as maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive germline BRCA-mutated patients. Maintenance rucaparib (NCT03140670) [50] and niraparib (NCT03553004) [58] are currently being evaluated through phase II clinical trials in patients with not only germline mutations but expanding it to somatic HRD mutations. Early results are optimistic, and these trials have the potential to further expand the patient population who can receive significant benefits through maintenance therapy.

PARP inhibitors as monotherapy were assessed among germline BRCA1/2-mutated ovarian cancer patients with olaparib (NCT01078662) [35], which showed durable response rates regardless of platinum sensitivity. Interestingly, two parallel phase II studies (NCT02511223 and NCT02677038) [34] studied olaparib as monotherapy in germline BRCA1/2-negative patients with DDR deficiency and showed a response in platinum-sensitive patients. Talazoparib in a phase Ib trial showed a good response in 20% of patients among germline BRCA1/2-mutated patients [55]. Rucaparib [51] in germline and somatic BRCA patients and veliparib [43] in germline BRCA or PALB2 mutations did not show significant response when used a monotherapy. Niraparib is currently under evaluation in two trials with germline and somatic HRD mutation patients with results yet to be published [57,58].

PARP inhibitors and multiple chemotherapy combinations have been evaluated with mixed results so far, and the majority of trials are still under evaluation. Veliparib, in combination with FOLFOX among metastatic pancreatic cancer patients, shows good tolerability with combination therapy, especially among patients with platinum-naïve, DDR deficiency, and patients with a family history. However, the efficacy of veliparib needs to be evaluated in a randomized fashion [44]. Veliparib with gemcitabine and cisplatin in BRCA/PALB2-mutated patients as well as in combination with FOLFIRI as second-line therapy among DDR deficiency patients did not show any significant benefit from the addition of veliparib [45,46]. There is also increased toxicity with combination therapy, as seen in NCT01296763 [37], of olaparib with irinotecan, cisplatin, and mitomycin.

Combination with immunotherapy, along with additional targeted therapy, is one of the new strategies under development. PARPVAX [59] trial is currently evaluating the combination of niraparib with nivolumab in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who have no disease progression with at least 16 weeks of platinum. Other combination trials such as the DAPPER [60] trial evaluating durvalumab (anti-PD-L1) with olaparib and NCT03637491 [56] trial evaluating avelumab (anti-PD-L1) with talazoparib are currently under investigation. Combination with targeted therapy is currently under evaluation with multiple agents. Trials in combination with olaparib, such as NCT03682289 [38] with AZD6738 (ATR kinase inhibitor), NCT03205176 [40] with AZD5153 (bivalent BRD4/BET bromodomain inhibitor), and NCT02498613 [39] with cediranib maleate (VEGF-TKI) are under investigation. The safety of such combinations could be a predominant issue, as seen in NCT02711137 [54], evaluating BET inhibitor as a single agent and in combination with multiple interventions, including rucaparib, currently terminated in view of safety issues.

Multiple resistance mechanisms have been hypothesized, leading to the failure of PARP inhibitors such as secondary mutations in BRCA genes resulting in the restoration of DNA repair mechanism, efflux pumps resulting in reduced intracellular PARP concentrations, epigenetic modifications, and loss of PARP expression, to mention a few [61]. Multiple newer PARP inhibitors are currently under development to overcome such resistance mechanisms. Other strategies, such as combination and sequential therapies, are more likely to improve the efficacy of PARP inhibitors.