Girls are losing out to boys in the fight against cancer — for two boys, only one girl got treatment at Mumbai’s Tata Memorial Hospital (TMH), the largest cancer hospital in India.

This gender gap is hampering paediatric cancer treatment among girls, say oncologists, and calls for measures addressing a range of issues from prejudice and awareness to even financial aid.

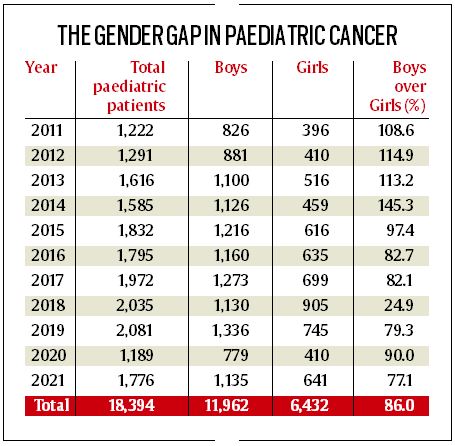

Records from TMH accessed by The Indian Express show that in the 10-year period between 2011-2021, a total of 18,394 children from across India were provided treatment at TMH Hospital. Of these, as many as 11,962 or 65% were boys, the remaining 6,432 were girls, making up for 35% of the total children.

These numbers tell a larger national story given that of the total paediatric patients, only 30% are from Maharashtra, the rest from other states.

Even at the Homi Bhabha Cancer Hospital, Varanasi, the second largest paediatric oncology centre among the TMCs – it runs a total of eight – the gender gap is wide. In 2019, of the 325 paediatric cancer patients, 197 or 60 per cent were boys and in 2020, of the 392 patients, 250 or 63 per cent were boys.

At TMH, Mumbai, over the last 10 years, the aggregate number of boys is nearly double that of girls who came for treatment at the hospital – the gap over 75% in each year except for 2018 where the number of boys was only 24 per cent more than that of girls. (See chart)

In comparison, the gender gap narrows in the adult population. According to data available, in 2017, of the total 34,906 cancer cases among the adult population who came to TMH, Mumbai, 57 per cent were male and in 2018, of the 36,095 adult cancer cases, 58 per cent were male.

This gap is a matter of concern given that the most common cancers in children don’t discriminate based on gender.

Said Dr Girish Chinnaswamy, paediatric oncologist at TMH: “Oral, breast or prostate cancers are minimal among children. Mostly, we witness blood cancers or cancer in bones, lungs, brain, among others which equally affect both genders.”

He attributed the gap to the possibility that “compared to boys, girls are less likely to be referred for diagnosis.”

Also, since early detection and timely treatment result in recovery in almost 80 per cent of the paediatric cases, oncologists said that girls who are not getting treated with cancer are losing their chance of survival and having a normal life like other children.

An illustrative example is that of a one-year-old girl from Latur who was detected with leukaemia — blood cancer — in 2021 and was undergoing treatment at the hospital. On March 7, 2021, however, her father got her discharged and took her to their native village. When social volunteers contacted him, he refused to continue with the treatment and the girl died in a few weeks.

“The family already had another daughter so citing the example of her future, they refused to travel back to Mumbai for treatment of the patient,” said Shalini Jatia, Secretary, ImPaCCT Foundation, Paediatric Oncology, TMC.

“No one says it directly. They beat around the bush then subtly pass on the message — a girl’s life holds lesser value,” she added.

The gender wise detection and treatment gap in India is in sharp contrast to that in developed economies where it is 1:1.

Said Dr S D Banavali, director of all the eight Tata Memorial Centres (TMCs) in India and professor at medicine and paediatrics at TMH: “The skewed sex ratio in cancer detection can be attributed to the social attitude where cancer-ridden girls aren’t prioritised for treatment. They don’t even reach the hospitals for treatment so cancer cases in girls go unreported.”

Banavali added: “Although the situation has improved, in cases of cancer in eyes and kidneys, where we need to remove the organs, parents refuse to do so citing that their girls won’t get married. Similar attribute is observed when we suggest amputations to save lives.”

“The sex-ratio in cancer detection is more skewed in northern parts of India. A study of AIIMS showed the ratio of boys to girls was 5:1,” said Dr Banavali.

The gender gap is also reflected in the rate of “treatment refusal and abandonment” (TRA) when it comes to girls. The TRA rate among boys in 2019 at TMH, Mumbai, was 2.3% compared to 2.7% among girls.

Of the 20 girls who dropped out of treatment, eight of the cases were due to gender-based disparity.

In 2020, the TRA rate was 3.2% among boys compared to 4.6% among girls. Of the 19 girl drop-outs, in eight cases, the reason was gender-discrimination. However, last year was an exception when TRA was higher in boys (1.9%) than girls (1.7%).

Often, even after arranging money for treatment of the girls, parents opt out. Anita Peter, executive director, Cancer Patients Aid Association, said that often parents refuse to upload the photos of girls affected with cancer on crowd-funding portals to collect money for treatment.

“They fear that if their relatives or neighbours get to know about cancer, their daughters won’t get married. So they deny financial help even if that costs the lives of their daughters,” she said.